Few things spark immediate concern in a parent quite like an unexplained rash or a worrying health query related to their newborn. When navigating the complexities of infant health, questions about rare conditions often arise. One such concern we frequently hear from caregivers centers on the possibility of their baby contracting shingles. This is a very understandable worry, especially since shingles is known to cause significant discomfort in adults.

The short answer is complex: While shingles is extremely uncommon in infants, it is technically possible. However, the circumstances required for a baby to develop shingles are highly specific and usually involve prior exposure to the same virus that causes chickenpox. Knowing the difference between the two conditions—and understanding the vital role of maternal immunity—can provide immense reassurance.

As experienced parenting editors, our goal here is not to alarm but to equip you with clear, trustworthy information regarding the Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) and its potential effects on the youngest members of your family. We will explore why shingles is rare in the first year of life, what the necessary precursors are, and when you should always reach out to your pediatrician for guidance.

The Core Connection: Shingles and the Varicella-Zoster Virus (VZV)

To understand the risk of shingles in infants, we first must understand its biological origin. Shingles, formally known as Herpes Zoster, is not a standalone virus. It is caused by the Varicella-zoster virus (VZV), which is the exact same virus responsible for chickenpox.

The critical distinction between chickenpox and shingles lies in how the virus is acting:

- Chickenpox is the primary, initial infection of VZV.

- Shingles is the painful reactivation of VZV later in life, after the initial chickenpox infection has resolved and the virus has laid dormant within the nerve roots.

For an adult or child to develop shingles, they must have had chickenpox at some point in the past—even if the case was so mild that it went unnoticed. The virus never truly leaves the body; it simply goes to sleep. Shingles occurs when something triggers that dormant VZV to wake up and travel along a nerve pathway, leading to the characteristic rash.

This biological pathway is why the question “Can babies get shingles?” is so unique. If shingles is a *reactivation* of a dormant virus, the baby must have been infected with chickenpox first.

Can Newborns and Infants Develop Shingles? The Highly Unusual Case

It is generally considered highly unusual for a healthy infant to develop shingles. Most cases occur in older adults (60+) or those with compromised immune systems.

However, when shingles does occur in the first year of life, it is typically linked to very early exposure to the Varicella-zoster virus.

Why Shingles is Rare in Healthy Infants

The primary reason most babies are protected is maternal immunity. If a mother has previously had chickenpox or has been fully vaccinated against it, she carries VZV antibodies. These antibodies cross the placenta during the third trimester, providing the newborn with what is often called “passive immunity.”

This protective shield usually lasts for the first six to twelve months of life and makes it very difficult for the baby to contract the initial VZV infection (chickenpox), let alone have the virus reactivate as shingles.

Scenarios Where Shingles May Occur in Infancy

While rare, medical literature notes instances where infants have developed shingles. These cases usually fall into specific categories:

- Early Life Chickenpox: The infant contracts chickenpox very early, perhaps within the first few weeks or months of life, before or as maternal antibodies begin to fade. If the VZV infection occurs early enough, the virus may reactivate later during infancy, leading to shingles. This initial VZV infection may have been so mild that it was never definitively diagnosed as chickenpox.

- Congenital VZV Syndrome (Different from Shingles): Exposure to VZV *in utero* (during pregnancy) can cause complex developmental issues, particularly if the mother contracts the primary infection during the first 20 weeks of gestation. This is a severe scenario, but it is technically a different presentation than typical shingles.

- Prematurity or Immune Compromise: Babies who are born prematurely or those with underlying conditions that affect the immune system may have lower levels of maternal antibodies or struggle to fight off initial infections, making them potentially more susceptible to VZV infection and subsequent reactivation.

In short, the baby must have the VZV virus already inside their system for shingles to develop. If it happens, it is often a sign of exposure to VZV sometime in the first year of life.

Understanding VZV Exposure: The Difference Between Chickenpox and Shingles Risk

It is important for parents to know that shingles lesions (the painful blisters) are contagious, but they transmit the chickenpox virus, not shingles itself. If an adult with active shingles lesions exposes an unprotected baby, the baby will typically contract chickenpox first, not shingles.

This is a critical distinction for caregivers:

- Risk to Baby from Active Chickenpox: High risk of contracting chickenpox.

- Risk to Baby from Active Shingles: High risk of contracting chickenpox (the primary infection). Shingles only develops in the baby later if the VZV reactivates.

The baby cannot directly “catch” shingles from an adult; they can only catch the underlying virus (VZV).

Protecting Your Baby from VZV

If someone in the baby’s immediate circle (a parent, grandparent, or sibling) has active shingles, the primary safety protocol is limiting contact until the lesions have scabbed over.

- Cover the Rash: Ensure all blisters are completely covered with clothing or a bandage. VZV transmission occurs through direct contact with the fluid in the blisters.

- Hand Hygiene: Practice extremely diligent hand washing, especially if touching the affected area.

- Avoid Direct Contact: If the rash is extensive or located somewhere that cannot be easily covered (like the face), the caregiver with shingles should minimize direct physical contact with the baby until they are no longer considered contagious.

This caution is heightened if the baby is very young (under 12 months) or has any known immune issues.

Recognizing Potential Symptoms: When to Seek Professional Guidance

Because shingles is so rare in infants, any blistering rash should be treated with immediate consultation with a pediatrician. Never try to self-diagnose skin issues in a baby.

If shingles were to occur in an infant, the symptoms may be different than the typical adult presentation. While adults often describe shingles pain as severe (a nerve pain that precedes the rash), infants obviously cannot communicate this.

Potential signs of a VZV-related rash in a baby may include:

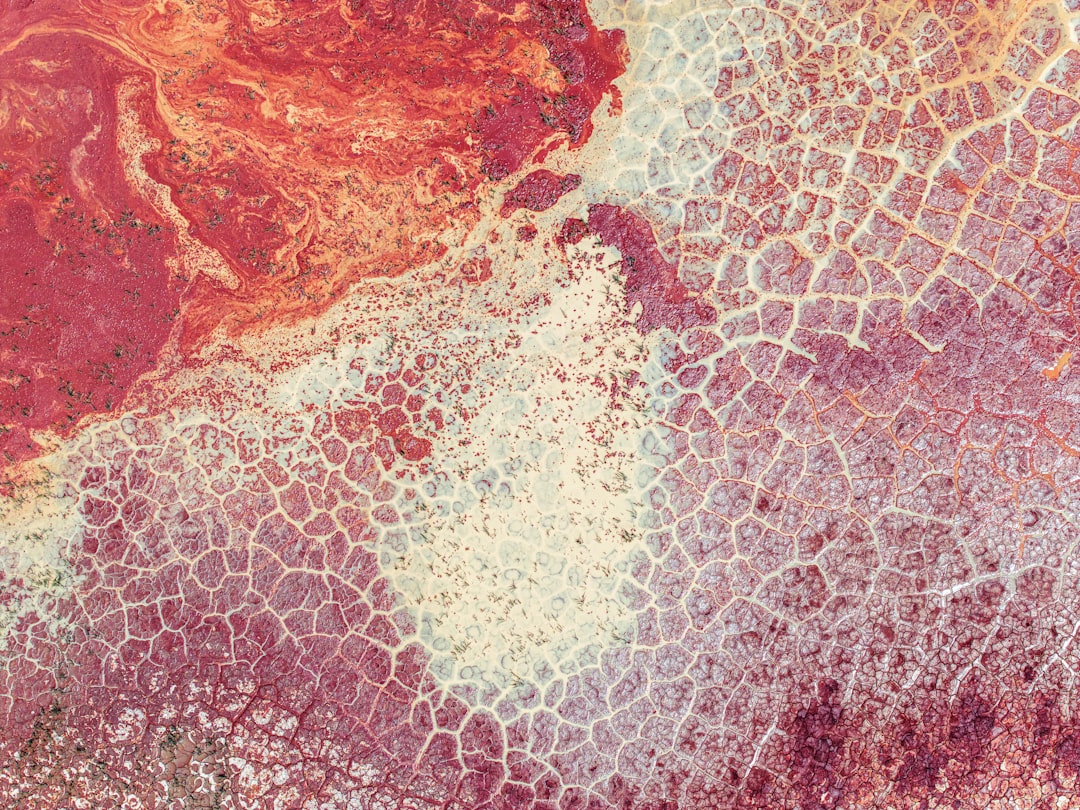

- Localized Rash: Unlike chickenpox, which presents as a generalized, widespread rash, shingles typically affects only a small, specific area or path on one side of the body, often appearing as a stripe or patch.

- Blisters: Clusters of fluid-filled blisters on reddened skin.

- Irritability: Increased fussiness or irritability, which may be related to discomfort or pain associated with the nerve path.

- Fever: Though not universal, a low-grade fever may accompany the viral process.

Again, it is crucial to remember that many common infant skin conditions, such as eczema or severe diaper rash, can sometimes look misleading. Only a qualified healthcare provider can accurately diagnose the source of a rash.

The Role of Vaccination and Prevention

Vaccination is our primary defense against VZV. For older children and adults, the chickenpox vaccine (Varicella vaccine) prevents the initial infection. For older adults, the Shingles vaccine (Zoster vaccine) helps prevent the reactivation of VZV.

Pediatric VZV Vaccination

In the United States, the VZV vaccine is typically administered to children starting around 12 to 15 months of age, followed by a booster dose between ages four and six years. This timing means that most babies under one year old have not yet received the vaccine, making them reliant on the passive immunity passed from their mother.

If your baby is approaching their first birthday, discussing the chickenpox vaccine schedule with your pediatrician is a routine part of well-child checks in 2026.

Maternal Vaccination and Immunity

If you are pregnant or planning to become pregnant, discussing your VZV history with your obstetrician is important. Knowing your immunity status helps ensure maximum protection for your baby during those vulnerable first few months. If a mother is non-immune to VZV, she should receive the vaccine before pregnancy or postpartum, as the live virus vaccine cannot be given during pregnancy.

When to Call a Doctor Immediately: Non-Negotiable Signs

While we aim to offer reassurance that shingles in infancy is rare, providing prompt medical care for concerning symptoms is non-negotiable. Always trust your instinct as a parent.

Please contact your pediatrician or seek urgent care immediately if your baby:

- Develops any widespread, blistering, or oozing rash.

- Has a fever (especially a high fever) accompanying a rash.

- Shows sudden, unexplained irritability or pain (pulling away from touch, prolonged crying).

- Has any sign of illness after being exposed to someone with active chickenpox or shingles lesions.

- Is lethargic, unresponsive, or feeding poorly.

Early identification of any viral infection is key to ensuring your baby receives the appropriate supportive care needed to manage symptoms safely.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) About VZV and Babies

Is shingles more serious for a baby than it is for an adult?

Because shingles is so unusual in infants, and their immune systems are still maturing, any VZV infection or reactivation warrants immediate medical attention. While cases of infant shingles are often mild and localized, VZV is generally more concerning in a baby under six months old than in a healthy older child due to the potential for complications.

If my baby was exposed to chickenpox, will they definitely get shingles later?

No, not definitively. If a baby is exposed to the VZV, they will first develop chickenpox. The vast majority of people who have had chickenpox never develop shingles, though the risk generally increases with age. Having chickenpox does mean the virus is dormant in the system, but reactivation is not guaranteed.

Can adults with the Shingles vaccine still infect my baby?

The Shingles vaccine (Zoster vaccine) helps protect the adult from getting shingles, but it does not transmit VZV to the baby. However, if the adult were to somehow contract chickenpox itself, or if they had an active shingles outbreak, they would be contagious via direct contact with the rash.

Is it safe for a pregnant woman to be around someone with shingles?

If the pregnant woman is immune to VZV (she has had chickenpox or the vaccine), it is generally safe, provided contact is avoided with the rash. If the pregnant woman is non-immune, she should avoid contact until the rash is scabbed over, and she should consult her obstetrician immediately, as contracting the primary VZV infection during pregnancy can pose risks.

How long does maternal immunity against VZV last?

Maternal antibodies provide passive immunity that offers significant protection, typically lasting anywhere from six to twelve months post-birth. This protection gradually fades, which is why pediatric vaccination against VZV is typically recommended around 12–15 months of age.

A Final Word of Reassurance

Hearing about viral illnesses like shingles can naturally cause anxiety, but remember that healthy infants are heavily protected, both by nature (maternal immunity) and by routine well-child checkups. If your baby develops any rash, fever, or change in behavior, contacting your pediatrician is always the safest and most effective step. Trust their expertise to guide you through accurate diagnosis and care, keeping your baby safe and comfortable in 2026.

***

Friendly Disclaimer

This article is for informational purposes only and does not replace professional medical advice. If you have concerns about your baby’s health or development, please consult your pediatrician or a licensed healthcare provider.